Like the White Whale itself, Herman Melville’s novel has been looming at the edges of my awareness for awhile now. Somehow I’d completely missed reading it in school, but references to it abound: in songs and operas, in cellphone commercials, in graphic novels, in superb modern-day treatises on whales, in meditations on the Cosmos, and now in a popular new book of philosophy (currently in my library queue) that uses the novel in its central argument. Melville’s whale casts a shadow on American culture: a shadow that has grown intimidating, with the unfortunate result that the story — a hefty block of text, rather off-putting in these hurried and distracted times — is more often praised than read. Last Christmas I resolved to dive into it, just to see what I’d make of it. I’m about halfway through it now; what follows is in no way systematic, but just a record of some of my thoughts and responses.

One of the first things that struck me is how progressive Melville’s sensibilities were, particularly towards the fascinating figure of the “savage” Queequeg. Ishmael’s attitude towards the cannibal harpooner is remarkable, given that Melville was writing in an America riven by arguments on race and hurtling headlong into civil war; amazed and astonished though he is at Queequeg’s foreignness, Ishmael is able to see past surface differences to find qualities to admire and a common humanity. Yes, there’s a bit of Noble Savage stereotyping, but it’s still a humanizing rather than a dehumanizing impulse:

Savage though he was, and hideously marred about the face — at least to my taste — his countenance yet had a something to it which was by no means disagreeable. You cannot hide the soul. Through all his unearthly tattooings, I thought I saw the traces of a simple honest heart; and in his large, deep eyes, fiery black and bold, there seemed tokens of a spirit that would dare a thousand devils. And besides all this, there was a certain lofty bearing about the Pagan, which even his uncouthness could not altogether maim. He looked like a man who had never cringed and never had had a creditor. […] It may seem ridiculous, but [his head] reminded me of General Washington’s head, as seen in the popular busts of him. […] Queequeg was George Washington cannibalistically developed.

Melville also reveals a little of his attitude towards philosophy, and his apparent disdain for conscious philosophizing (or perhaps simply for putting on intellectual airs rather than living out one’s ideas without pretension):

Here was a man some twenty thousand miles from home, by the way of Cape Horn, that is — which was the only way he could get there — thrown among people as strange to him as though he were in the planet Jupiter; and yet he seemed entirely at his ease; preserving the utmost serenity; content with his own companionship; always equal to himself. Surely this was a touch of fine philosophy; though no doubt he had never heard there was such a thing as that. But, perhaps, to be true philosophers, we mortals should not be conscious of so living or so striving. So soon as I hear that such or such a man gives himself out for a philosopher, I conclude that, like the dyspeptic old woman, he must have “broken his digester.”

And while I don’t think they’re necessarily gay, Ishmael and Queequeg share an intimate emotional and physical relationship that would raise the eyebrow of many a conservative today. Melville, to his credit, doesn’t bat an eye, and portrays this as an entirely valid expression of friendship and love:

He seemed to take to me quite as naturally and unbiddenly as I to him; and when our smoke was over, he pressed his forehead against mine, clasped me round the waist, and said that henceforth we were married; meaning, in his country’s phrase, that we were bosom friends; he would gladly die for me, if need should be. […]

How it is I know not; but there is no place like a bed for confidential disclosures between friends. Man and wife, they say, there open the very bottom of their souls to each other; and some old couples often lie and chat over old times till nearly morning. Thus, then, in our hearts’ honeymoon, lay I and Queequeg — a cosy, loving pair.

(I have to say, though, that Melville’s enlightened attitude towards “the other” only goes so far. Much later, we learn that Ahab’s mystery crew of Orientals “were of that vivid, tiger-yellow complexion peculiar to some of the aboriginal natives of the Manillas; — a race notorious for a certain diabolism of utility, and by some honest white mariners supposed to be the paid spies and secret confidential agents on the water of the devil, their lord, whose counting-room they suppose to be elsewhere.” And the crew’s leader, Fedallah, “was such a creature as civilized, domestic people in the temperate zone only see in their dreams, and that but dimly; but the like of whom now and then glide among the unchanging Asiatic communities […] — those insulated, immemorial, unalterable countries, which even in these modern days still preserve much of the ghostly aboriginalness of earth’s primal generations […] when though, according to Genesis, the angels indeed consorted with the daughters of men, the devils also […] indulged in mundane amours.” So far these characters seem irredeemably foreign and inscrutable, and I’ve yet to see Melville extend to them the same humanizing gesture he did to Queequeg; perhaps his circle of concern never extended that far.)

Melville’s take on religion is fascinating. I’m not sure yet how to take Father Mapple’s thundering sermon in Chapter 9; it grounds the story in the Biblical myth of Jonah, but it’s not clear to me yet whether Melville uses it to establish the themes of the novel or to set up religious assumptions to be questioned and undermined. What I do know is that his capacity for tolerance is remarkable, and that his moral imagination goes beyond what I assume are the conventional Christian attitudes of his time. See, for instance, Ishmael deciding to fully befriend the pagan Queequeg and even share in his rituals of worship:

I’ll try a pagan friend, thought I, since Christian kindness has proved but hollow courtesy. […]

I was a good Christian; born and bred in the bosom of the infallible Presbyterian Church. How then could I unite with this wild idolator in worshipping his piece of wood? But what is worship? thought I. Do you suppose now, Ishmael, that the magnanimous God of heaven and earth — pagans and all included — can possibly be jealous of an insignificant bit of black wood? Impossible! But what is worship? — to do the will of God — that is worship. And what is the will of God? — to do to my fellow man what I would have my fellow man to do to me — that is the will of God. Now, Queequeg is my fellow man. And what do I wish that this Queequeg would do to me? Why, unite with me in my particular Presbyterian form of worship. Consequently, I must then unite with him in his; ergo, I must turn idolator. So I kindled the shavings; helped prop up the innocent little idol; offered him burnt biscuit with Queequeg; salamed before him twice or thrice; kissed his nose; and that done, we undressed and went to bed, at peace with our own consciences and all the world.

What impresses me here is that Melville — while no secularist, and certainly no atheist — nevertheless attaches no importance to the particular rituals and requirements of different faiths; his overarching principle is the Golden Rule, valued by believers and nonbelievers alike. His desire isn’t to convert Queequeg to his beliefs, nor to convert himself to Queequeg’s, but to share in the experience of worshiping both ways — to see what the other sees, and to share what he sees with the other.

Another lengthy and wonderful passage: Ishmael criticizing “Ramadan” and, by extension, all man-made religious strictures (though Queequeg’s “Ramadan” seems more like an animist ritual to me, and Melville seems to be confusing and conflating non-Christian faiths). The argument that fasting leads to half-starved thoughts is great, and the final sentence is a keeper:

“Queequeg,” said I, “get into bed now, and lie and listen to me.” I then went on, beginning with the rise and progress of the primitive religions, and coming down to the various religions of the present time, during which time I labored to show Queequeg that all these Lents, Ramadans, and prolonged ham-squattings in cold, cheerless rooms were stark nonsense; bad for the health; useless for the soul; opposed, in short, to the obvious laws of Hygiene and common sense. I told him, too, that he being in other things such an extremely sensible and sagacious savage, it pained me, very badly pained me, to see him now so deplorably foolish about this ridiculous Ramadan of his. Besides, argued I, fasting makes the body cave in; hence the spirit caves in; and all thoughts born of a fast must necessarily be half-starved. This is the reason why most dyspeptic religionists cherish such melancholy notions about their hereafters. In one word, Queequeg, said I, rather digressively; hell is an idea first born on an undigested apple-dumpling; and since then perpetuated through the hereditary dyspepsias nurtured by Ramadans.

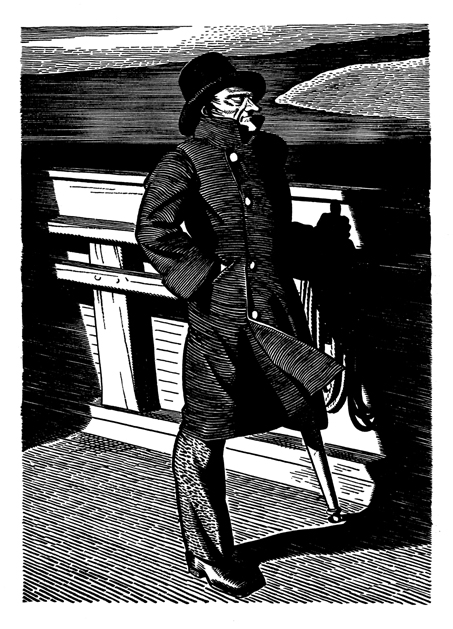

There’s so much else: the iconic Captain Ahab, of course, maimed and stark and grim as a lightning-scarred tree — and still perhaps the greatest study of monomaniacal obsession in all of literature; the frequent disquisitions on the whaling industry and the nature of the whale itself (amusing, now, in the age of advanced marine photography, to consider Melville’s certainty that the sperm whale can never be seen in its living entirety); the blood-chilling legends surrounding the White Whale; even an extended meditation on whiteness itself, on how the color can embody evil (or death, or nothingness) as well as good — “at once the most meaning symbol of spiritual things, nay, the very veil of the Christian’s Deity; and yet […] the intensifying agent in things the most appalling to mankind.”

(In writing this, could Melville have intended a critique of the notion that whites were a superior race, all nobility and goodness? He certainly seems happy enough to employ the whale as a symbol for a great many things — as have all critics of Moby-Dick ever after — and yet, ironically, he turns right around and denounces those who “might scout at Moby Dick as a monstrous fable, or still worse and more detestable, a hideous and intolerable allegory.”)

Just a couple more notes for now:

Melville is funny. (“At least to my taste,” as Ishmael says.) His comment about hell being “an idea first born on an undigested apple-dumpling” is Exhibit A. Ishmael’s mistaking an offer of a clam-chowder dinner for a meal of merely one clam, and his panic over Queequeg’s immobility during his pagan rituals, make for a fine comedy of errors. And Melville turns out to be splendid at spinning out elaborate puns:

Why it is that all Merchant-seamen, and also all Pirates and Man-of-War’s men, and Slave-ship sailors, cherish such a scornful feeling towards Whale-ships; this is a question it would be hard to answer. Because, in the case of pirates, say, I should like to know whether that profession of theirs has any peculiar glory about it. It sometimes ends in uncommon elevation, indeed; but only at the gallows. And besides, when a man is elevated in that odd fashion, he has no proper foundation for his superior altitude. Hence, I conclude, that in boasting himself to be high lifted above a whaleman, in that assertion the pirate has no solid basis to stand on.

And finally, a more philosophical passage. On a dull, lazy afternoon, Queequeg and Ishmael pass the time weaving a “sword-mat” — which Melville turns into a brief but astonishing meditation on fate, chance, and free will:

[I]t seemed as if this were the Loom of Time, and I myself were a shuttle mechanically weaving and weaving away at the Fates. There lay the fixed threads of the warp subject to but one single, ever returning, unchanging vibration, and that vibration merely enough to admit of the crosswise interblending of other threads with its own. This warp seemed necessity; and here, thought I, with my own hand I ply my own shuttle and weave my own destiny into these unalterable threads. Meantime, Queequeg’s impulsive, indifferent sword, sometimes hitting the woof slantingly, or crookedly, or weakly, as the case might be; and by this difference in the concluding blow producing a corresponding contrast in the final aspect of the completed fabric; this savage’s sword, thought I, which thus finally shapes and fashions both warp and woof; this easy, indifferent sword must be chance — aye, chance, free will, and necessity — no wise incompatible — all interweavingly working together. The straight warp of necessity, not to be swerved from its ultimate course — its every alternating vibration, indeed, only tending to that; free will still free to ply her shuttle between given threads; and chance, though restrained in its play within the right lines of necessity, and sideways in its motions modified by free will, though thus prescribed to by both, chance by turns rules either, and has the last featuring blow at events.

Magnificent. The debate still rages on between those who say our destinies are written (either by the will of God or by evolution’s blind hand); those who fear that all we do and think and feel is meaningless, the mere artifacts of electrical impulses and chemical interactions; and those who say that free and independent human intention is real, and still counts for something. Melville, nearly two centuries ago, took all of these understandings of human existence and wove them together into a vision more complete and more true.

Yes, we’re children of necessity and chance, of ancient biological imperatives and accidental mutations; and our intelligent consciousness arises entirely out of physical processes in the three-pound mass lodged in our skulls (as an amazing exhibition at the Museum of Natural History makes clear). But this doesn’t devalue who we are, nor does it make us unwilling slaves to blind process. “If there’s nothing here but atoms,” Carl Sagan said, “does that make us less, or does that make matter more?” And as Philip Pullman contends: “We are conscious, and conscious of our own consciousness. We might have arrived at this point by a series of accidents, but from now on we have to take charge of our fate. Now we are here, now we are conscious, we make a difference. Our presence changes everything.”

We live at the nexus of necessity, chance, and free will; all play a part in our experience of the world. Melville had the incredible insight to see this, and the audacity and generosity to embrace it.

Perhaps a follow-up post later, once I’ve finished the book.

Quelle weird, part 2. After the coincidence today with the TED video (bluejaysway.wordpress.com/2012/03/09/the-best-ted-talk-ever/ ), I saw “Reading Moby Dick” listed in the right sidebar. In the course of the SAME conversation I mention in the TED comment, another colleague also brought up Moby Dick. He’s reading it to his daughter. Funny how the world works, isn’t it.

Yeah, that happens to me a lot. 🙂

How old is your colleague’s daughter? I’m having difficulty imagining that Moby-Dick would be an accessible story to most pre-teens…

(I did finish the book, by the way, but just haven’t written a post about the second half of it…)

I’m not sure how old his daughter is — he keeps his private life quite private — but I think 10 to 13-ish. He did mention that she was not that into it, mostly because of the philosophical discussions in between the plot points.

I’m now feeling inspired to pick up Moby Dick again. I read it in college and didn’t really get it. But I had an epiphany about what it all meant while I was writing my final exam essay. It was a really great idea and I got an A+ on the test. Unfortunately, I had pulled an all-nighter cramming for said exam, with the result that I’ve never been able to remember what I wrote.

And I am digesting the great cetacean myself finally after living almost 60 years on this good Earth. I like your use of images. I tend to write and then leave the images to others. It makes my blog harder on the visual cortex. I posted my first comment on the great adventure on 6/18/13,